Ahead of COP 27, global leaders are still not making the grade on climate change education

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Sign up

Sign up for the Worlds of Education newsletter.

Thank you for subscribing

Something went wrong

As attention focuses on Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt for the 27th UN Climate Change Conference (or COP27), climate change education advocates have their work cut out for them.

To date, 140 updated, revised, or new Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) [1] have been submitted to the UNFCCC, representing 166 (or 86%) Parties to the Paris Agreement, including countries in the European Union. Of these NDCs, every country has made a failing grade on the Education International Climate Change Education Ambition Report Card. Just under a third of these NDCs mention climate change education—the majority of which are countries with greater climate vulnerability and where children bear the highest climate risks. Globally, young people and future generations are in desperate need of a climate change education champion. But no clear forerunner has emerged.

Since my last update, two much-anticipated countries have submitted their NDCs: Egypt and India. However, both countries’ NDCs scored an F (see this first edition for an overview of the scoring metrics). These two last-minute report cards are significant for two reasons.

First, because Egypt holds the Presidency of COP27. Its leadership on climate change education is vital to sustaining the momentum that the UK’s Presidency of COP26 catalyzed in Glasgow with the first ever joint ministerial meeting between ministers of environment and ministers of education. There, ministers made pledges to invest in “education for a sustainable future,” and youth activists pressed the importance of investing in the climate resilience of present and future generations, especially of girls, through an investment in climate change education. While Egypt’s NDC lacks the commitment needed for the country to steward this momentum forward at COP27, other actors like UNESCO will help to ensure there are opportunities in Sharm El-Sheikh for countries to advance progress and build energy around climate change education.

Second, India’s failing score is significant because the country is the 3rd largest emitter of greenhouse gases, it regularly experiences the acute impacts of climate change, and it is home to the world’s largest youth population—who also bears some of the highest climate risks in the world. Moreover, in 1991 India’s Supreme Court mandated that environmental education and the teaching of sustainability be infused throughout the primary and secondary curriculum; however, the country has struggled to implement this mandate. Calling out climate change education in its NDC could have helped to mobilize domestic and international resources to the country’s education system. But it failed to take the helm. In fact, its NDC failed to mention education at all. Next to Egypt, India’s much-anticipated updated NDC was our last chance as a global community for a climate heavyweight to prioritize education as a climate strategy.

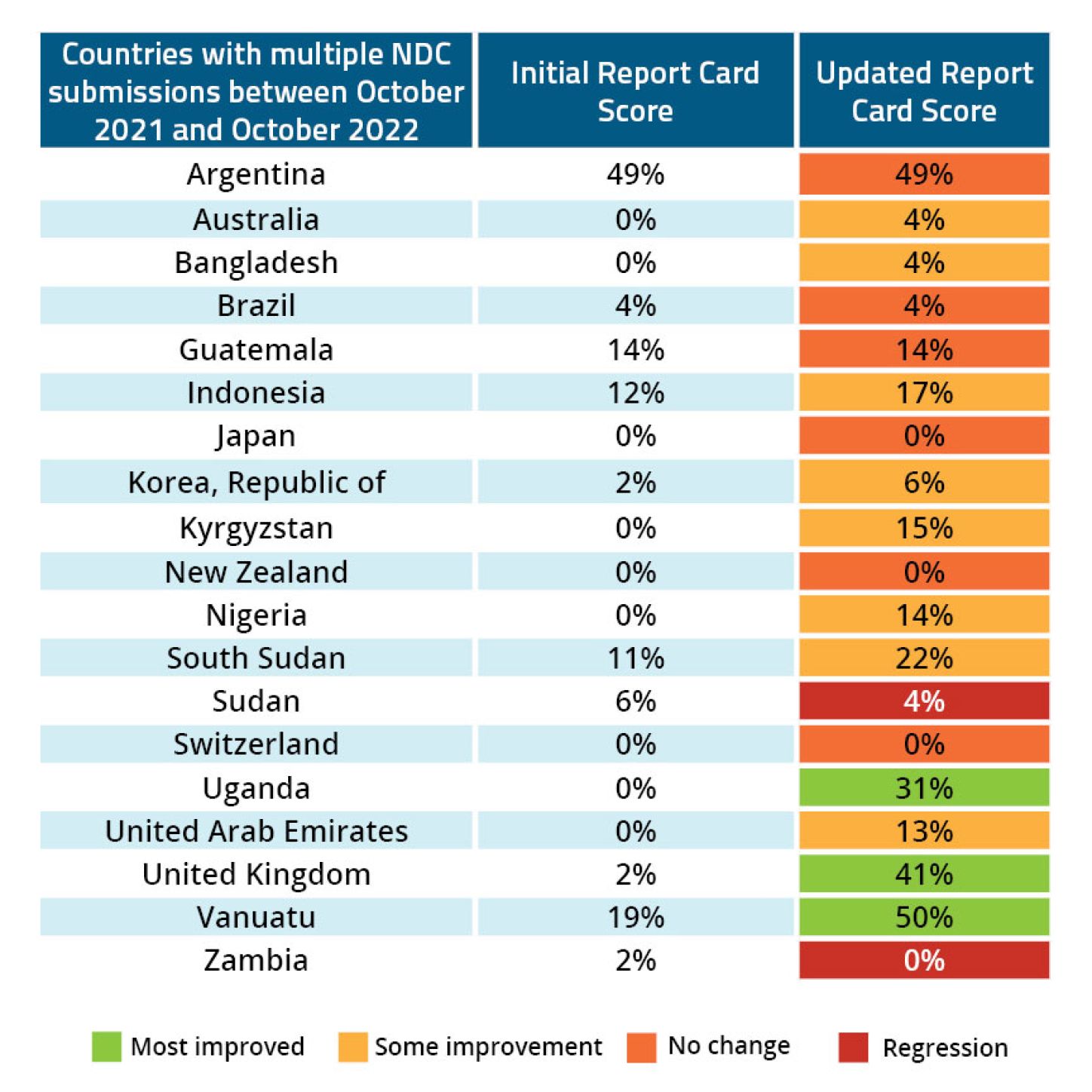

But the picture isn’t entirely bleak. Vanuatu’s updated NDC (with a score of 50%) now joins the top-scoring NDCs alongside Cambodia (58%), the Dominican Republic (51%), and Colombia (50%). Indeed, over the course of this study, 19 countries submitted a second or third updated or revised NDC. Several of these showed improvements from an extremely low starting score. Here are a few more hopeful highlights:

Most improved

- The United Kingdom’s updated NDC improved 39 percentage points (moving from an F to a B, on a curved scale). The country’s NDC made its greatest strides in its attention to education—highlighting the recent passing of the Department of Education’s Strategy for Sustainability and Climate Change for Education and Children’s Services, which lays out Britain’s plan to build young people’s knowledge of the natural world and green skills for green jobs. If the UK’s improved NDC is any indication as to what holding the COP Presidency can do to a country’s climate change education policy ambition, let’s hope the same effect will be experienced by Egypt.

- Uganda’s updated NDC improved 31 percentage points (moving from an F to a C, on a curved scale). It names the education sector as one of the country’s 13 priority climate adaptation sectors, calls for the integration of climate change into the national curriculum, and points to the Ugandan National Climate Change Learning Strategy. While Uganda’s updated NDC calls for monitoring indicators to be disaggregated by gender, it does not specify that climate change education in the country should be gender responsive. This is despite the country ranking 29 on the Girls’ Education Challenges Index.

- Vanuatu’s updated NDC also improved by 31 percentage points (moving from a D to an A, on a curved scale). It is one of only 5 NDCs that recognizes young people’s right to education, and one of only 2 NDCs that makes this reference in the context of climate-related disruptions (Argentina being the other). Vanuatu’s updated NDC integrates timebound targets for improving the climate resilience of education infrastructure, attends to the integration of indigenous knowledge in the curriculum, and recognizes the unique vulnerabilities that climate change poses on girls’ education and girls’ life outcomes, thus further impacting their access to important climate information.

Honorable mention for improvement made

- The United Arab Emirates’ updated NDC deserves special attention. While it did not improve on its climate change education ambition (nor its attention to education, more generally), it did make strides in its attention to empowering youth, especially girls and women, as agents of change in climate action. Specifically, the UAE’s updated NDC goes into great detail to describe the country’s efforts at building climate resilience and adaptive capacity by investing in young people’s, especially young women’s, capacity for green innovation and green jobs. Such attention should not go unnoticed, as this marginal improvement can be widened further through advocacy over the next year as the country prepares to take the mantle of the Presidency of COP28.

While the education community should celebrate these small wins, it should not be forgotten that every country’s NDC scored a failing grade. Cambodia’s NDC remains the highest scoring, at 58%. And where countries have had a second (or even third) chance during the course of this study to strengthen their climate change education policy ambition, only 3 have done so significantly. Of the 19 countries that submitted multiple updated or revised NDCs, 6 countries’ NDC scores didn’t change (meaning no progress, nor any regression), and 2 countries (Sudan and Zambia) actually scored worse on their climate change education policy ambition the second time (see Table below).

The lack of country-level climate change education leadership is alarming. But Uganda, the United Kingdom, and Vanuatu have shown that it is possible to ramp up one’s ambition in a short time. As the world focuses on COP27, let’s work together to raise the climate change education ambition of every country.

Nationally Determined Contributions are countries’ national plans of action for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to the impacts of climate change.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any official policies or positions of Education International.